Arizona’s WWII Japanese Relocation Camps

By Russ Sherwin

To undo a mistake is always harder than not to create one originally but we seldom have the foresight.

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1943 upon visiting the Gila River, Arizona camp

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which granted the military the power to

“. . . prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.”

This came about because of the perceived threat of Japanese people living on the West Coast possibly aiding an invasion there by Japan, or spying for Japan. Although this order was ultimately to result in the “relocation” of nearly 120,000 Japanese-American citizens, most of them American born, nothing in EO-9066 mentioned any specific ethnic or racial group.

Rumors were in abundance. “Of course they are spies.” “They’re signaling to submarines off-shore.” “They’re planning an invasion.” None of this was true, but almost anything, no matter how benign could trigger a rumor that would then spread like wildfire.

There was a report of a white lantern being waved near the coast nearly every night. When this was tracked down, it turned out to be a Japanese, alright, an old farmer who had to make a trip to the outhouse most every night and took his lantern with him.

Another was a report of a red light swinging at night. This turned out to be a light hung on a barbed wire fence. It had been there for years to warn of the fence.

There were “white, cone shaped missiles” in a field in Washington state that were pointed directly at the Boeing Aircraft facility. These were white cone-shaped shields placed over tomato plants.

On March 18, a month after EO-9066 was signed, Executive Order 9102 established the War Relocation Authority—WRA—under the Office for Emergency Management, which reported directly to the President:

“1-The Director of the War Relocation Authority is authorized and directed to formulate and effectuate a program for the removal, from areas designated from time to time by the Secretary of War or appropriate military commander under the authority of Executive Order No. 9066 of February 19, 1942, of the persons or classes of persons designated under such Executive Order, and for their relocation, maintenance, and supervision.”

Again, in all of the eleven paragraphs of this order, no mention is made of persons of Japanese descent or any other ethnicity. However, under the authority granted by EO-9066 and EO-9102, on April 1, 1942, the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army Wartime Civil Control Administration issued Civilian Exclusion Order No. 5 which was posted on lamp posts, mailboxes, buildings, signboards and in all public places everywhere on the West Coast where Japanese people were known or likely to live. Each was tailored to the specifics of the area and set up specific control centers where people were to report. The example below is for part of the city of San Francisco, California:

INSTRUCTIONS

TO ALL PERSONS OF

JAPANESE

ANCESTRY

LIVING IN THE FOLLOWING AREA:

All that portion of the City and County of San Francisco, State of California, lying-generally

west of the north-south line established by Junipero Serra Boulevard,

Worchester Avenue, and Nineteenth Avenue, and lying generally north of the

east-west line established by California Street, to the intersection of Market

Street, and thence on Market Street to San Francisco Bay.

All Japanese persons, both alien and non-alien, will

be evacuated from the above designated area by 12:00 o'clock noon, Tuesday

April 7, 1942.

No Japanese person will be permitted to enter or leave

the above described area after 8:00 a.m., Thursday, April 2, 1942 without

obtaining special permission from the Provost Marshal at the Civil Control

Station located at:

1701 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, California

The Civil

Control Station is equipped to assist the Japanese population affected by this

evacuation in the following ways:

1. Give advice and instructions on the evacuation.

2. Provide services with respect to the management, leasing, sale, storage of

other disposition of most kinds of property including: real estate, business

and professional equipment, buildings, household goods, boats, automobiles,

livestock, etc.

3. Provide temporary residence elsewhere for all Japanese in family groups.

4. Transport persons and a limited amount of clothing and equipment to their

new residence, as specified below.

The Following Instructions Must Be Observed:

1. A

responsible member of each family, preferably the head of the family, or the

person in whose name most of the property is held, and each individual living

alone must report to the Civil Control Station to receive further instructions.

This must be done between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., Thursday, April 2, 1942, or

between 8:00 a.m. and 5 p.m., Friday, April 3, 1942.

2. Evacuees must carry with them on departure for the Reception Center, the

following property:

a. Bedding and linens (no mattress) for each member of the family.

b. Toilet articles for each member of the family.

c. Extra clothing for each member of the family.

d. Sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups for each member of the family.

e. Essential personal effects for each member of the family.

All items

carried will be securely packaged, tied and plainly marked with the name of the

owner and numbered in accordance with instructions received at the Civil

Control Station.

The size and number of packages is limited to that which can be carried by the

individual or family group.

No contraband items as described in paragraph 6, Public Proclamation No. 3,

Headquarters Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, dated March 24, 1942,

will be carried.

3. The United States Government through its agencies will provide for the

storage at the sole risk of the owner of the more substantial household items,

such as iceboxes, washing machines, pianos and other heavy furniture. Cooking

utensils and other small items will be accepted if crated, packed and plainly

marked with the name and address of the owner. Only one name and address will

be used by a given family.

4. Each family, and individual living alone, will be furnished transportation

to the Reception Center. Private means of transportation will not be utilized.

All instructions pertaining to the movement will be obtained at the Civil

Control Station.

Go to the Civil Control Station at

1701 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, California,

between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., Thursday, April 2, 1942,

or between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., Friday, April 3, 1942,

to receive further instructions.

J.

L. DeWITT

Lieutenant General, U. S. Army

Commanding

By this order, posted April 1, the Constitutional Bill of Rights was effectively suspended for persons of Japanese heritage, even if they were natural born American citizens, which most of them were. They were ordered to report to their designated Civil Control Station by April 3. Here they received their orders and found out where they were to be sent. Evacuation followed within a couple of weeks. Many Japanese living on the West Coast were fearful of something like this happening as soon as they heard about the Pearl Harbor bombing on December 7, 1941. From that date until most of them had been forced from their homes, farms and businesses was at most 4 months. Families were kept together for the most part.

Bill Hosokawa, an American-born journalist, age 27 at the time, was sent first to a WRA Assembly Center in Puyallup, Washington, then to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center 12 miles east of Cody, Wyoming. He describes some of the losses that people suffered:

“There were a lot of cultural things—there were letters from Japan from the members of the family that had to be left behind. Things like that were all burned or dumped because the fear that any connection with Japan would be interpreted as sentimental ties, cultural ties, maybe political ties with the old country. The physical loss was in furniture, cars—there are authenticated cases of used furniture dealers driving down the street in the Japanese residential areas, “Hey you Japs! You’re gonna get kicked outa here tomorrow. I’ll give you ten bucks for that refrigerator. I’ll give you fifteen bucks for that piano. I’ll give you two dollars and fifty cents for that washing machine.” And the material loss of the evacuation, just the physical material loss has been estimated at 300 million dollars, in 1942 dollars!”

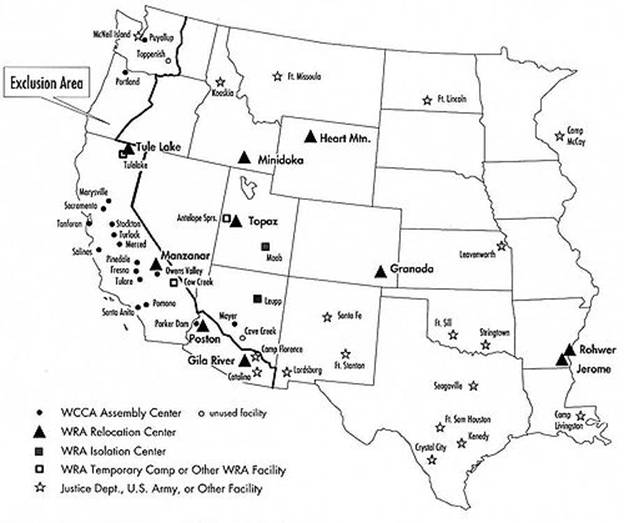

A total of ten WRA Relocation Centers and two WRA Isolation Centers were established, along with a number of temporary camps and WRA Assembly Centers which served as collection points from which people would be sent to the real camps. The difference between a Relocation Center and an Isolation Center was one of security: Isolation Centers had higher security and armed guards. There are reports that troublemakers were sent to an Isolation Center for violations as simple as calling a Caucasian nurse an “old maid.”

Above is a map showing the WRA facilities. Note the exclusion area includes the entire state of California and the western halves of Oregon and Washington. But Arizona, not normally considered a West Coast state, was also affected. The line designating Military Area 1, which divided communities between forced relocation zones and areas excluded from relocation, entered Arizona near Needles, California, and zigzagged down various roads to Wickenburg. Entering the Phoenix-metro area, the line headed south along Grand Avenue, turned east at Van Buren Street, then went south at Mill Avenue before crossing the Salt River. At Apache Boulevard, it headed east again, through Tempe and Mesa, to the Miami-Globe area, and onward to the Arizona–New Mexico border. Japanese Americans relocated from the Phoenix area were sent to either Gila River or Poston, while those not relocated were restricted to certain areas[1].

The State of Arizona boasted two Relocation Centers, Poston and Gila River; and one Isolation Center at Leupp. Poston was 12 miles south of Parker, Arizona. It was the third largest city in Arizona after Phoenix and Tuscon when it was in full operation. The Gila River Relocation Center, about 50 miles southeast of Phoenix, was the fourth largest city in Arizona.

All of these camps were hastily built. Most camps held something on the order of 10,000 to 15,000 people. From the time EO-9066 was issued until people started being distributed out to the camps was about two months. Construction was in process as people were arriving. The Poston Relocation Center was built in three weeks beginning on March 27, 1942 using 5000 workers on two shifts. It consisted of three units separated by three miles each, along a north-south axis. They were officially named Posten I, Posten II and Posten III, but the evacuees quickly named them “Roasten, Toasten and Dustin.”

The contractor was Del Webb, now famous for building housing in Sun City, Arizona, among others. Del Webb had a large work force already mobilized for military contracts, and built Luke Air Force Base near Phoenix in March 1941. However, the relocation center was Del Webb's biggest challenge up to that time. Webb had a construction job in progress at Blythe, and when he got the contract to build the camps he diverted his crew to Parker. With equipment brought up from Blythe, the initial ground clearing was done in one day.[2] Guard towers were not constructed at Poston, as they were at the other relocation centers; here they were considered unnecessary because of the isolated location, in the desert at the end of a road.

Believed to be the hottest camp created by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), Poston reported an unconfirmed all-time high of 145 degrees on July 17, 1942. The structures, resembling army barracks, were built with double roofs in an attempt to counter the fierce Arizona heat, but they were covered with black tarpaper which probably negated any effect of the double roof. Pine boards were specified, but because pine was in short supply, redwood was substituted. The boards shrank quickly in the heat and exposed cracks and knotholes that allowed an aggressive population of rodents, insects and reptiles to invade the barracks. Residents attempted to counter this by nailing tin can lids over the holes.

Some quotes from residents in the camps:

"We didn’t have running water in the barracks; there was no indoor plumbing. One of the first things that women with children did was to order chamber pots from the Sears Roebuck catalog."—Elaine Hibi Bowers, Poston Internee.

"They were raw and ugly camps. I hated Poston the first day I saw it, and I hate it today."—Nisei Internee at Poston

Compared to other WRA locations, Gila River had an attractive appearance with barracks of plastered beaverwood and red fireproof shingles. It was considered somewhat of a showplace compared to other WRA camps. Both Canal Camp and Butte Camp, subdivisions within Gila River, were designed as linear blocks of barracks with intervening recreation areas. Fourteen barracks in each camp housed around 300 people each and were divided into crude 20 by 25 foot family apartments.

Only one guard tower was ever constructed at Gila River, and it was quickly abandoned and torn down, and the barbed wire perimeter fences as well. Camp administrators were lenient in allowing residents access to Phoenix and recreational opportunities in the surrounding desert.

Outsiders

were upset that the Japanese, even though held against their will were fed and

housed by the government and had access to meat, milk and other commodities

that were rationed or in short supply to the general American populace. To some

extent this may have been a valid complaint, but the evacuees were certainly

not “coddled” as some newspapers reported.

Outsiders

were upset that the Japanese, even though held against their will were fed and

housed by the government and had access to meat, milk and other commodities

that were rationed or in short supply to the general American populace. To some

extent this may have been a valid complaint, but the evacuees were certainly

not “coddled” as some newspapers reported.

Eleanor Roosevelt[3] made a surprise visit to the camp in April, 1943 to look into charges that the Japanese Americans there were given special treatment. Her observations were published in Collier’s Magazine on October 10, 1943. In it, she described the camp’s austere living conditions and commented:

I can well understand the bitterness of people who have lost loved ones at the hands of the Japanese military authorities, and we know that the totalitarian philosophy, whether it is in Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy or in Japan, is one of cruelty and brutality…. These understandable feelings are aggravated by the old time economic fear on the West Coast and the unreasoning racial feeling which certain people, through ignorance, have always had wherever they came in contact with people who are different from themselves.

To undo a mistake is always harder than not to create one originally but we seldom have the foresight. Therefore we have no choice but to try to correct our past mistakes and I hope that the recommendations of the staff of the War Relocation Authority, who have come to know individually most of the Japanese Americans in these various camps, will be accepted.

…A Japanese American may be no more Japanese than a German-American is German, or an Italian-American is Italian, or of any other national background. All of these people, including the Japanese Americans, have men who are fighting today for the preservation of the democratic way of life and the ideas around which our nation was built.

We have no common race in this country, but we have an ideal to which all of us are loyal: we cannot progress if we look down upon any group of people amongst us because of race or religion. Every citizen in this country has a right to our basic freedoms, to justice and to equality of opportunity. We retain the right to lead our individual lives as we please, but we can only do so if we grant to others the freedoms that we wish for ourselves.

It is interesting that Eleanor seems, with her comments, to project a completely different view of the Japanese-Americans than that held by her husband, who signed the orders that forced their incarceration, and his administration.

At its peak the Moab, Utah, WRA Isolation Facility held 49 men. In early 1943 the inmates at Moab were moved to the Leupp Isolation Center in northeastern Arizona about 30 miles northwest of Winslow, an abandoned Indian boarding school on the Navajo Indian Reservation.

Most of the Moab inmates were moved to Leupp by bus. Five of those held in the Grand County jail, however, were forced to make the 11-hour trip confined in a four by six foot box on the back of a flat-bed truck. Leupp was basically a medium security prison with four guard towers, a cyclone fence topped with barbed wire, and 150 military police who outnumbered the inmates by more than 2 to 1.

Evacuees in Poston and Gila River were transferred to Leupp for such infractions as drawing pictures that did not meet administration approval, leading a work walk-out, or trying to form a union. Francis Frederick, in charge of internal security at the isolation center, remarked in a letter to a friend "What [the WRA] call dangerous is certainly questionable".

The United States was not alone in perpetrating this horror upon their Japanese citizens. Canada instituted similar measures:

“On February 24, 1942 an Order-in-Council passed under the War Measures Act gave the [Canadian] Federal Government the power to intern all "persons of Japanese racial origin." A "protected" 100-mile (160 km) wide strip up the Pacific coast was created, and men of Japanese origin between the ages of 18 and 45 were removed and taken to road camps in the British Columbian interior or sugar beet projects on the Prairies.” Source: Wikipedia

Below is a poem, That Damned Fence, widely

circulated at the Poston Camp, author unknown:

THAT DAMNED FENCE

(anonymous poem circulated at the Poston Camp)

They've sunk the posts deep into the

ground

They've strung out wires all the way around.

With machine gun nests just over there,

And sentries and soldiers everywhere.

We're trapped like rats in a wired

cage,

To fret and fume with impotent rage;

Yonder whispers the lure of the night,

But that DAMNED FENCE assails our sight.

We seek the softness of the midnight

air,

But that DAMNED FENCE in the floodlight glare

Awakens unrest in our nocturnal quest,

And mockingly laughs with vicious jest.

With nowhere to go and nothing to do,

We feel terrible, lonesome, and blue:

That DAMNED FENCE is driving us crazy,

Destroying our youth and making us lazy.

Imprisoned in here for a long, long

time,

We know we're punished--though we've committed no crime,

Our thoughts are gloomy and enthusiasm damp,

To be locked up in a concentration camp.

Loyalty we know, and patriotism we

feel,

To sacrifice our utmost was our ideal,

To fight for our country, and die, perhaps;

But we're here because we happen to be Japs.

We all love life, and our country

best,

Our misfortune to be here in the west,

To keep us penned behind that DAMNED FENCE,

Is someone's notion of NATIONAL DEFENCE!