My Story

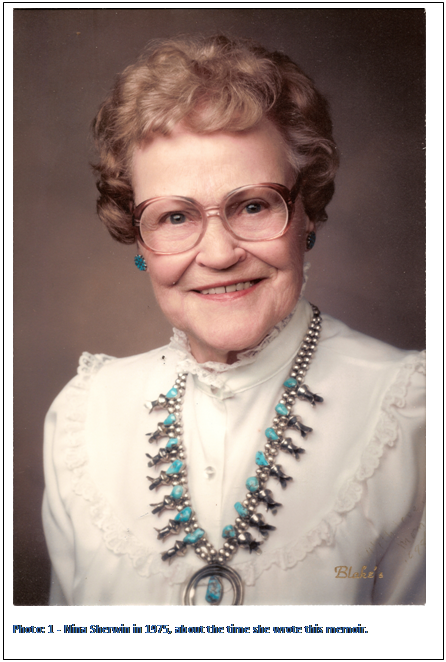

Written By Nina Frances Russell Sherwin (about 1975 I think)

Edited by Russ Sherwin, Nina’s son, March 2010

This

is a simple story of part of my life; from whence I came, and where I went from

there, so you perhaps can see what makes me tick. For background, I will go to

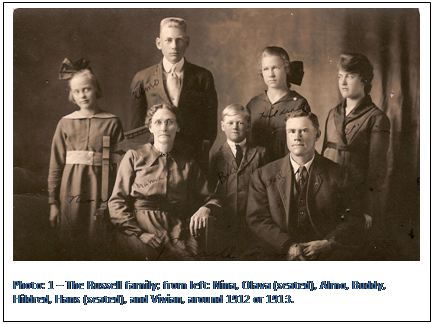

my grandparents. Anton and Caroline Thompson Rushold (later changed to Russell

by some of the family) were both born near Sandsvar, Norway, married later in

America and lived in Brooten, Minnesota where Anton was a tailor and a farmer.

My mother’s parents were Ole Olson Bente, and Johanna Maria Nilsdatter Bjerke,

both also born in Norway. They farmed in and around Brooten. My father, Hans

Theodore Russell, was born September 17, 1875, in Fairibault, Minnesota, and

farmed near Brooten. My mother, Olava Elise Bente, was born August 26, 1869,

near Brooten. They were married April 15, 1898 and farmed near Brooten for

several years. The two older children were born there: Almo Franklin, 1899; and

Ora Vivian (always called Vivian) in 1901. The family then moved to North

Dakota for a few years where Hildred Evangeline was born in 1903. After that

they moved to Warroad, Minnesota, where I, Nina Frances, was born in 1906, and

George Clifford (always called Buddy or Bud) in 1908.

This

is a simple story of part of my life; from whence I came, and where I went from

there, so you perhaps can see what makes me tick. For background, I will go to

my grandparents. Anton and Caroline Thompson Rushold (later changed to Russell

by some of the family) were both born near Sandsvar, Norway, married later in

America and lived in Brooten, Minnesota where Anton was a tailor and a farmer.

My mother’s parents were Ole Olson Bente, and Johanna Maria Nilsdatter Bjerke,

both also born in Norway. They farmed in and around Brooten. My father, Hans

Theodore Russell, was born September 17, 1875, in Fairibault, Minnesota, and

farmed near Brooten. My mother, Olava Elise Bente, was born August 26, 1869,

near Brooten. They were married April 15, 1898 and farmed near Brooten for

several years. The two older children were born there: Almo Franklin, 1899; and

Ora Vivian (always called Vivian) in 1901. The family then moved to North

Dakota for a few years where Hildred Evangeline was born in 1903. After that

they moved to Warroad, Minnesota, where I, Nina Frances, was born in 1906, and

George Clifford (always called Buddy or Bud) in 1908.

During our years there, Papa was a surveyor on the Lake of the Woods, a saloon keeper, city electrician, and a farmer—at separate times, of course. He was a very smart and handy man who could do almost anything he put his mind to, and had quite an inventive turn of mind. In later years, I once commented to him that I guessed he could do almost anything except be a minister of the gospel, and he replied, “Oh, Hell! I could be that too, if I wanted to.” He was a man of few words and quite gruff when he did speak. I have to admit I was afraid of him most of my life—not physically, but that I would do something to incur his displeasure. One thing that did contribute to my being afraid of him, and this was physical, was that, when I was very small, and he had been away surveying for some time, when he came home, he had a mustache, which he hadn’t had before. Enough to scare anybody! Anyway, anent [in reference to] his gruffness, when it came time for bed and we kids were still around, he would say, shortly and gruffly, “Go to bed!” And we went! Mama was a religious woman, Lutheran, of course, quiet, friendly and good neighbor to all. She had much hardship in her life, not the least of which was leaving all her family of parents and nine sisters when they moved to North Dakota.

I

have always thought of North Dakota as the real jumping off place and am glad I

wasn’t born there. Such a harsh climate—so hot in the summer and so very cold

and blizzardy in the winter. Of course, Warroad wasn’t that much better either

as far as winter goes. We often hear on the weather reports that Warroad is the

coldest spot in the nation. And the summers were hot enough and also

mosquito-ey. We used to have smudges out in the yard to keep the mosquitoes

away. And mosquito nets over our beds at night. This place of my childhood is

still dear to my heart, but I would not want to ever go back there to live. I

still have residual effects from chilblains we all had every winter. These

result from getting your feet very cold, almost freezing, which we would do in

playing outdoors and not having sense enough to come in in time. If you once

had chilblains you were more easily subject to them the next year, so we had

them every winter. The toes and heels would swell up, turn purplish, and itch

and burn and hurt. The remedy at that time was to soak the feet in kerosene. I

now have one toe which swells up and itches and hurts when my feet get just a

little chilly. I recently asked a druggist in Cody about something to relieve

this, and he had never heard of chilblains; and perhaps some of you never have

either.

I

have always thought of North Dakota as the real jumping off place and am glad I

wasn’t born there. Such a harsh climate—so hot in the summer and so very cold

and blizzardy in the winter. Of course, Warroad wasn’t that much better either

as far as winter goes. We often hear on the weather reports that Warroad is the

coldest spot in the nation. And the summers were hot enough and also

mosquito-ey. We used to have smudges out in the yard to keep the mosquitoes

away. And mosquito nets over our beds at night. This place of my childhood is

still dear to my heart, but I would not want to ever go back there to live. I

still have residual effects from chilblains we all had every winter. These

result from getting your feet very cold, almost freezing, which we would do in

playing outdoors and not having sense enough to come in in time. If you once

had chilblains you were more easily subject to them the next year, so we had

them every winter. The toes and heels would swell up, turn purplish, and itch

and burn and hurt. The remedy at that time was to soak the feet in kerosene. I

now have one toe which swells up and itches and hurts when my feet get just a

little chilly. I recently asked a druggist in Cody about something to relieve

this, and he had never heard of chilblains; and perhaps some of you never have

either.

Our house was new. I have no recollection of what we lived in before, or while it was being built, or of moving into it. It looked quite imposing for that time, a two story white house with three porches, one in front and one on each side. There was a good sized yard and a large garden spot with raspberry bushes along one side. We had an outdoor privy, as did most everyone, which we indelicately called the “backhouse.” When we went out there at night, in winter, we would take a lighted lantern which was a great comfort, for light as well as the warmth it gave. In winter, Mama used to tack wool cloth around the toilet seats so they wouldn’t be so cold—another great comfort. We did use mail order catalogs for toilet paper. That was later than the corn cob days, which we never did use, thank Heaven. For water, we had an artesian well, with a hand pump in the kitchen sink, which was a lot better than many of our neighbors, some of whom came there for water.

As I said, the house looked big, and we thought it was huge. Downstairs was a parlor, with all the parlor furniture: settee, piano, fern stand, etc, oh, yes, a center table complete with hand crocheted cover, knick-knacks, and all. This room was not used very much. The dining room was where we did our school work, reading, playing cards, etc. Like a family room is now. There was a wood stove heater there, and we dressed and undressed there before going up to our bedrooms, which were not heated. There was a large kitchen where we ate most of the time, Mama and Papa’s bedroom, and a sort of all purpose small room where the stairway was to the upstairs. Up there were two bedrooms with two walk-in closets. Almo and buddy had one room and closet, Viv, Hildred and I the other. Viv slept alone; she being oldest girl was “the boss.” Hildred and I slept together in one bed, which was fine with us.

In 1966, Almo, Hildred and Mark, Buddy, Wylie and I all went to Warroad (Viv couldn’t make it). The first time any of us but Almo had been back since we left in 1918. It was devastating to see how everything had shrunk! Even the Warroad River, but especially the house! The people who lived there, the son and daughter-in-law of our old neighbors, let us go in and look around. It had been changed some, but the basic size of the rooms and all was the same, and they were unbelievably small. It was a traumatic experience, really, and I wished after that that we either had not gone or had stayed longer and perhaps gotten a better perspective on it all. A nostalgic trip like that was should not be rushed, but the men in the party, even Buddy, were not as enthralled with it as Hildred and I were, so we stayed only two nights and didn’t do or see all we should have while there. We did see the “Nina Boat” that Dad had used in surveying, and was also our pleasure boat. A remarkable thing that it was still there after all those years. How, or why, it was named the Nina instead of Vivian or Hildred, I don’t know, but do wish I did. One never thinks to ask about these things until it is too late and there is no one left to ask.

Back to life in Warroad—one vivid memory is about Viv and I having our tonsils out. This must have been around 1914 or ’15. Dad (Papa, I mean) took us to Roseau, a town not too far away, which had a hospital. We were put in separate rooms and Viv had her surgery first. I remember hearing this terrible moaning sound, and finally realizing it was Viv, which scared the wits out of me, of course. Then the Doctor appeared to take me into the operating room, with his apron all covered with blood. That just about put me over the edge, and when they put the ether mask over my nose and mouth, I fought them every inch of the way. They finally prevailed, my tonsils were removed, and I was back in my bed. I was not fully aware though, (or was I?) because when they put a bowl of water on my bed—to wash in, I guess, but I never found out—I hauled off and sent the whole thing flying across the room. I was not a bit contrite about this act, and thought they fully deserved it!

Now, through desire, or necessity, we sold the “big house” and moved to a farm about three miles from town. During the school year, we kids stayed in a house the folks rented in town, not far from where we had lived before. We always walked to school, which was about a mile and a half, I would judge; there were no school busses. We took our lunches and in winter, hot soup or cocoa was available for one penny. This was a welcome addition to our cold sandwiches. I don’t remember even hearing about a Thermos bottle at that time.

The next thing was the War; the Big One, World War I, the one to make the world safe for democracy. Almo and a group of senior high school boys enlisted and left for training, just before graduating. They were given their diplomas in advance. Almo subsequently was sent to France, where he served for about a year.

In the meantime, Papa had contracted to do some road work with his team of horses. But with the war had come high prices on machinery and everything necessary in this work and he went broke. As there was not much for the future there anyway, he decided to move to Montana. Mama took Buddy and me on the train to visit all the relatives in and around Brooten—west and a little north of Minneapolis— before moving. I don’t know why it was such a secret; maybe it really wasn’t, but I actually didn’t know we were going to move. I was having so much fun with my friends in Warroad, wading in the water, trying to swim, etc.—it was late May or early June—and I didn’t want to go and visit my cousins or my uncles or my aunts or anyone else. But we went, and I kept looking forward to getting back to Warroad. That was never to be. Papa, Viv and Hildred, in our new Ford, met us in Middle River, Minnesota as we were on the train going home, and from there we went on to Montana. I felt really betrayed, and never did quite get over not getting back home to Warroad.

I talked to Hildred some years ago about this move, but it was so long ago she couldn’t remember any details about it either. Nothing about packing up and shipping our belongings or why we were met in Middle River. Perhaps Papa thought it would be easier on Mama not going back. I’m sure it was heart-breaking enough for her the way it was, having to leave her home and all her friends and go to a strange country. The trip was uneventful, and we really enjoyed it. It was June and the countryside was green and pretty. As kids do yet, Buddy and I gathered rocks along the way, mostly by the roadside, so you can imagine their rare beauty. I remember there was a big detour near Miles City where the Yellowstone River had flooded and there was water and mud everywhere.

You will notice that, upon entering Montana, Papa promptly became Dad. It was “green” and “Norwegian” to say “papa.” Anyway, while planning the move to Montana, Dad had talked of the farming country around Judith Basin. So I don’t know how we happened to end up near Billings—Laurel, actually—for a few days. Talk about a jumping off place. Laurel has improved somewhat, but at that time it was just a little, dirty railroad town, which we hated. We ended up in a small house near Hesper, a station between Laurel and Billings for that summer, fall and winter. We just lived there is all; Dad didn’t work. I don’t suppose there was any work to be had around there, especially during the winter.

Viv and Hildred were both in Billings, working for their board and room while going to high school. It was the winter of 1918-19 and a mean one it was, not only for the harsh weather, but because of the first flu epidemic. Miraculously, none of us had it. Buddy and I attended Elder Grove School, a good-sized school about 2 miles from our house. Bud was in the 5th grade, I in the 7th and our first experience in a country school. It has been remodeled, built on, and improved and is still operating. I really liked this country school and I guess Bud did too. The best part for me was getting acquainted with Margaret Keithly (now Stewart) who lived on a farm about half way between our place and the schoolhouse. That farm and land west of it is now the Yellowstone Boys and Girls Ranch. Margaret and I would meet at her road and walk to school together. We talked endlessly, telling stories, movies, etc. She had to tell the movies because I hadn’t been to any. On the way home it was the same thing. We were such friends, and loved each other dearly (we still do) and we had such giggly good times together. I also “fell in love” that year with a boy who went to school there. People scoff at kids falling in love at that age, but it seems pretty real to the ones involved. Margaret had her “crush”, too, so we had that to talk about endlessly, too.

Almo came home from France that spring and we moved to a dry land ranch up on the rims, not a great distance from Hesper. It was a bleak place and that is putting it kindly. No trees except in the draws, and they were all small scrubby evergreen types. Prairie dogs were everywhere and before anything could be done with the land they had to be gotten rid of. We could get free poisoned bran from the Ag[riculture] Department for this purpose, and we put it out by hand in each prairie dog hole. That did get rid of the animals so the land could be cultivated and wheat planted as well as some hay. We had four horses, Nickel and Daisy, the parents and King and Nancy the offspring. They were our machinery except for threshing the wheat.

Besides the prairie dogs, this country was rattlesnake infested, being dry and rocky, a rattlesnake paradise. Many a time we jumped away from a shock of wheat or a haycock when we heard that warning rattle. But I was never terrified of them, as the stories I had heard in Minnesota about rattlesnakes had made me think they were huge, at least as big as a boa constrictor, so when I saw their size it was really rather disappointing. We killed a lot of them but managed to keep a healthy respect for them as potential killers of us.

I think of this uncompromising land, with its prairie dogs, rattlesnakes, hordes of grasshoppers, barren of trees and grass, no visible water in comparison to Minnesota with all its lakes and rivers, green trees of many species, hundreds of wild flowers and the variety of berries and wonder how my poor mother felt when she first laid eyes on it—to say nothing of the shack we had to live in.

It was probably a kind fate that took her away from it that first summer up there, 1919. She was taken to Billings to the hospital for gall bladder surgery and died during the operation. Viv always said an inept surgeon was to blame, and she may have been right. I was staying at Keithlys for a few days, and I remember Dad driving in to get me and what a shock it was when he said Mama had died. You think your Mama is always going to be there, especially when you’re 13 years old. That was June 29th, 1919.

I spent a lot of time at Keithlys that summer, and Margaret’s mother and father were like second parents to me. I loved them, especially Mrs. Keithly, and loved staying there. Margaret and I used to take a kerosene lamp into her closet with us so we could read and talk and her folks wouldn’t see a light under the bedroom door. It’s a wonder we didn’t set the place on fire! We also used to get tobacco and cigarette papers from the hired man’s bunk house and go out in the field and smoke. The way we rolled them though, the smoking didn’t last long. A thought in passing—a few years later, this hired man was the first man I ever danced with, and many years later, I met up with him again when I was at the Trail Shop and he was working at Holm Lodge. His name was Barney Ronan.

Except for Mama being gone, that summer wasn’t too awfully bad, as everyone else was home, even Almo. Viv and Hildred were home from school, of course. We had a bad hail storm which did away with any crop we might have had that first year, and we were really poor. As aforementioned, we lived in a real shack, with a lean-to made of canvas, where we girls slept in the summer—not usable in winter. Water was from a well, with a pump outdoors. And, of course, an outdoor privy (the word John came much later). We had a wood burning cook stove which also provided heat, and kerosene lamps. We did have a gasoline lamp later, with mantles, which gave much better light. At least it was one step up!

When Viv and Hildred went back to school that fall, I had to learn how to make bread, which we made in 10-loaf batches to last a week, ‘till Saturday came again. Of course, I left the learning process until the last minute and the first batch I made was literally all over the house. Can you picture how much dough there is in a 10-loaf batch of bread? We had a bread pan that was half as big as a wash tub (some of you probably don’t even know how big a wash tub is!) and that was full. Then transfer that to a table to knead it and keep adding flour, because the dough was too soft, and maybe you get the picture. Besides that, I was trying to get it done and cleaned up before Dad got back from wherever he had gone. I must say that eventually I made darned good bread. Dad did most of the other cooking. We had lots of mush, and lots of beans. (I still love beans!)

Speaking of washtubs, as above, that was the way we did the washing—heated water on the stove and washed the clothes in the tub, using a scrub-board. We learned to save on water by using it first for baths, then soaking and washing clothes, then finally to scrub the floor.

Buddy and I went to school at another country school, called Cove School, about five or six miles down in the valley from where we lived. We rode double on horseback, trading off between King and Nancy. King was a little more spirited and ornery and would kick up his heels when someone got on behind the saddle. It wasn’t what you could call bucking, but it was enough to terrify me, and my stomach was always tied in a knot on the days we had to ride King. A neighbor boy rode with us too, and sometimes he would let me ride his horse and he would ride double with Buddy. A charitable act for which I was duly thankful.

Cove was a one-room school with all grades and one teacher—a real come down from Elder Grove. I didn’t like the teacher very well either. In retrospect, I think she was probably a pretty good sort, but not easy to be friendly with, and with me being shy and backward also, it was a bad combination. On account of the weather, I stayed overnight with her once in a while (she lived at the schoolhouse) and that was real punishment for me—I would rather have faced the storm! We had so little in the line of clothing that this teacher felt badly about it, I guess, and told me to tell our father that we could apply for some aid along that line. I told Dad, but he said a flat “No” to that idea. At that point I think I wouldn’t have minded so much accepting a little charity. At Christmas time, there was a program at school, which I was in, and I decided I had to have curls in my hair for the occasion. So Buddy and I trudged up to Masons, after dark, without saying anything to Dad, to have Mrs. Mason put my hair up in rag curlers. Dad found we were gone and came up after us. I don’t know why Dad blamed Buddy for this, as he was clearly just accompanying me, but he escorted us out of Mason’s house taking Buddy by the ear! I was so scared I wet my pants! I suppose I shouldn’t even tell things like that, but this is my story and I’m just telling it like it was.

Somehow the four of us, Dad, Almo, Buddy and I muddled through the winter. Dad and Almo slept in the only bed; Buddy and I on the floor with no mattress, just a quilt underneath. I’m not trying to make this sound pitiful, but it really was a primitive existence without much comfort or joy.

In June, having completed the 8th grade, I had to go to Billings to take State Board Exams. I stayed overnight with Viv who was living with Dr. and Mrs. Allard and family, and working for her room and board while finishing her senior year in high school. I passed the exams, so I was ready for high school, academically, at least. Of course, I had to work for my room and board, too. It was difficult to find a place to stay, and I was two weeks late starting school, so had that to make up. Talk about a “green freshman”—and from the country at that! I had a tan cotton dress with blue organdy insets in the skirt—OK as far as it went. The cold weather outfit was a navy blue skirt and a red flannel middy blouse, also made by Viv. I did find a place with the Billings Street Commissioner and his wife and family of several small children. He would take me out to the ranch once in a while on weekends, but was a little too “friendly”, so after Christmas I found another place. This was with a prominent Billings lawyer, his wife and 2 daughters, one in college and one about a year younger than I. I stayed there through that year and the next, going home, of course, during the summer.

During these high school years, and mostly after I wasn’t working for my room and board any more, I often stayed overnight or weekends with another dear friend, Fern Shackelford (Canney), who lived on a farm west of Billings. Her folks were like second parents to me also, and made me feel at home there. The two of us did plenty of giggling, too, and I’m sure made the older folk wonder what in the world could be that funny! Fern and Margaret and I were together a lot all through high school and they stayed with Viv and me often, too, after we had an apartment.

Hildred quit school after her junior year in h igh school to stay with Dad on the ranch. Viv taught one year up at Bainbridge in northern Montana. The next year, she started working as receptionist and records librarian at Dr. Allard’s office, where she worked for many years.

The first part of my junior year in high school Viv and I had a sleeping room, with “kitchen privileges” in an upstairs apartment with a widow and her small son. She was a little weird, kind of mean, and very stingy. She put newspapers under the rocking chair rockers so they wouldn’t scratch or wear out the floor. She turned the hall carpet upside down so the “good side” wouldn’t get worn out. To take a bath—and no more than once a week, and Viv and I together at that—we had to heat water in kettles on the stove to put in the tub, as using hot water from the faucet was too extravagant and we would use too much. After she had done something mean to us, or her little boy, she would take to her bed and would actually get knots on her head as big as a large marble. I always thought they were the beginnings of horns! After a spell like that, she would be extra nice, and ask Viv and me to have dinner with her, so of course, we always would. She was an excellent cook and our meals, with what skimpy privileges we had in her kitchen, were nothing to write home about, so we did enjoy hers.

In the meantime, Dad, Almo and Hildred moved out from the place on the rims to a place east of Billings to what we all refer to now as “The Ranch[1]”, and where most of you have been. They built a house, which was small, but a palace compared to the shack on the rims. There was a good spring and pond right there, so there was water in the house, but still an outdoor privy for a few years. Bud and I spent summers out there, and it always seemed like home. We all went to dances around there, in Ballantine, Worden, Huntley and had lots of good times—still poor, but not destitute.

In the second half of my junior year Viv rented an apartment at 307 South 28th street, a fairly nice neighborhood at that time, pretty crumby now. So, Bud, now in high school also, and I lived there with her. It must have been quite a drain on Viv to pay rent, buy groceries for all three of us and help Bud and I with our clothing and expenses, as I don’t believe Dad was able to help much, if any. I babysat some, and earned a little spending money, but there wasn’t much spent on anything but necessities.

I graduated from high school in 1924, not really prepared for making a living at anything. I attended Normal School in billings that summer (this Normal School was the very small beginning of Eastern Montana College, presently in Billings). This summer school enabled me to teach school on a “permit”. The Superintendent of Schools sent me to apply for a school about half way between Billings and Roundup and I was hired. It was a one-room school, log, with a sod roof, water in a bucket, and of course, the usual outdoor toilet. I rode horseback from where I roomed and boarded to the school house. This was with an elderly lady, 70 at the time, [who] looked and acted every bit her age, and smelled like it too. She had a grown up son with tuberculosis who slept outdoors in a tent. That was what they did for TB at that time. An adult nephew of hers lived there also. I had a bedroom of my own until it really got cold, then the tubercular son moved in and took over my bedroom and I had to sleep with the old lady. Ick!

There were eight children in school, five from the same family, who lived right near the school. The kids were all right and I really liked them, but I couldn’t take the rest of it, so I quit at Christmas time. After Christmas, I taught at Cove school where I had attended 8th grade. There were two teachers, Isabel Stewart and [me]. She had the lower four grades and I the upper four. This was much better and I liked working with Isabel, whom I had known before (Leslie Stewart’s sister). This was a one-room schoolhouse, which made it a little difficult, as all 8 grades were in the same room. And also harder as some of the same students I went to school with there were now my students. But we finished up that year there pretty well. The school was moved then, a mile south, added onto, and called Baseline. So it was a two room school with the upper and lower grades separate and with two teachers. I taught with a Mrs. Perkins that year and she drove from Billings and I paid my share of the transportation expenses. But that was enough teaching for me.

During part of this time I was going to night school at Billings Business College, taking typing, shorthand, and bookkeeping. I never quite finished that, as I got a job in the circulation department at the Billings Gazette. There I used my typing experience a little, but not a whole lot, and didn’t need the shorthand or bookkeeping at all. As you can see by this, I do type some now, but have to look, not exactly hunt and peck, but certainly would not be classed as a typist.[2]

By this time Buddy was out of school at the ranch and working around there. Viv and I had a bigger and better apartment on South 28th Street. This part of town wasn’t too bad then, not like it is now, and we were pretty comfortable. The apartment was nice (it’s still there) on the ground floor, small kitchen, dining room, living room with a gas fireplace, a sun room which was Viv’s bedroom. I slept on a daybed in the dining room area. Of course there was a bathroom too. For a little while Margaret stayed with us and later another girl who also worked at the Gazette. This helped with expenses, and life wasn’t such a struggle.

I wasn’t going to tell this, but lest I be branded a “quitter”—quitting teaching, and now quitting the Gazette job (I was there two years)—I have to tell you why I left there. This girl who worked at the Gazette also, and lived with us, became a very dear friend of mine. But after a while, there seemed to be something “funny” going on. One night Hildred and Viv and I went to a show, and returned early—you know we did this on purpose—our boss at the Gazette came roaring out the back door in a great hurry with clothing in disarray, and that was what had been going on, right in our apartment. This was long ago, when morals were not as loose as they are now, and a situation like that was not tolerated. And I was devastated to be so betrayed by one for whom I cared so very much. She left the apartment, of course, and I quit working at the Gazette. The boss knew we had seen him; in fact I told him that was why I was leaving. I couldn’t work with either of them after that, and there wouldn’t have been any future for me there anyway.

For a few months I didn’t work anywhere. Then a new (rival) newspaper started up and I started working there. What I didn’t know was that it was just a temporary and political deal for an election year, and the job and the paper lasted only a few months.

Now it is the summer of 1929. Viv, Hildred, Ingeborg Enevoldsen (later Almo’s wife) decided to take a trip through Yellowstone Park. I don’t remember much about the car, but I guess it was Dad’s, and Hildred and Ingeborg did the driving. The first night we stayed in Cody at the Irma Hotel, just “lurking” around town, having dinner, etc. The next day we went out to DeMaris Hot Springs and had a swim in the medicinal waters.[3] We had reservations at Holm Lodge for that night, and it was only about 40 miles or so up Northfork, so we were in no hurry. As we crossed the old bridge near where Wapiti Lodge and the Wapiti Post Office is now, I smelled gasoline and commented on how I loved the smell of it—that was from smelling it when the boats used to come up the river in Warroad. About that time Ingeborg said something was wrong with the car. The Simpers family had a place by the highway, across from the school house, where they served chicken dinners, and we stopped there to see what we could do about the car. Chella Hall came along and said she would go up to Mountain View and get Mr. Jenkins to come and see if he could fix it. He was a good mechanic and soon had us ready to go.

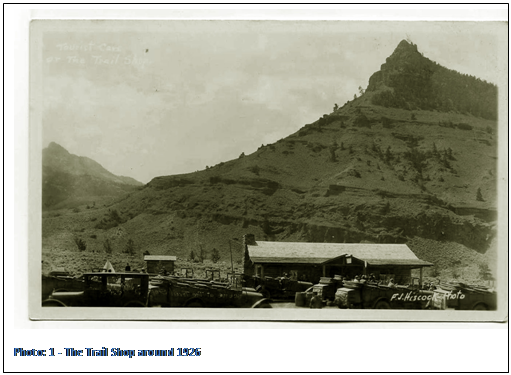

Chella

said we had better stop at the Trail Shop and call Miss Shawver at Holm Lodge

and let her know we were coming, as she would take a dim view of four girls

coming in late. So we stopped at the Trail Shop to use the phone, and who

should be there but Elaine Neville, who was then married to Harry Huntington. I

had known her in Billings, as she had stayed a while with her cousin Ida May

Sessions, who lived in an apartment next to Viv’s and mine. We used the phone

and visited a while and I asked Elaine if they needed any help there, that I

was just out of a job. They didn’t, and we went on to Holm Lodge and the rest of

the trip through the Park. I wish I had some pictures, but Viv had the only

camera, which was a movie camera of Dr. Allard’s. She took quite a few

pictures, but I saw them only once and I don’t know what happened to them. I do

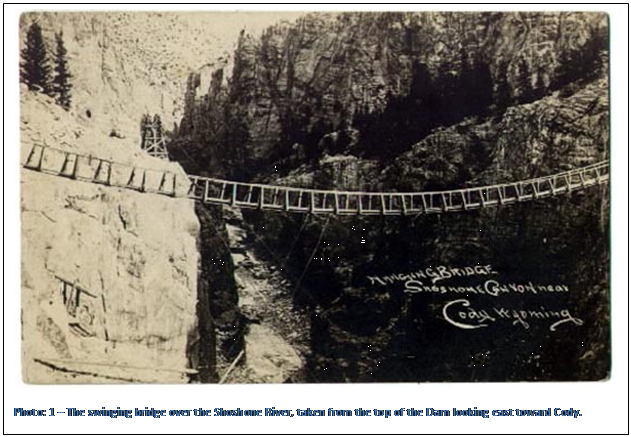

remember we walked across the swinging bridge in the canyon[4] which was

posted with a “No Trespassing” sign. It was scary, as it swayed when we walked

on it. I suppose that was a challenge of some kind to do that, and besides it

gave us a real good look up the canyon. I also remember hand feeding a bear,

which was one of the pictures. Stupid kid—it’s a wonder I still have two hands!

The bears were more used to that then, though, and they weren’t as dangerous as

they are now. We saw most everything there was to see in the Park—went to dances

at night, moonlight picnics, horseback rides, etc. with the kids who worked up

there. It was a fun week.

Chella

said we had better stop at the Trail Shop and call Miss Shawver at Holm Lodge

and let her know we were coming, as she would take a dim view of four girls

coming in late. So we stopped at the Trail Shop to use the phone, and who

should be there but Elaine Neville, who was then married to Harry Huntington. I

had known her in Billings, as she had stayed a while with her cousin Ida May

Sessions, who lived in an apartment next to Viv’s and mine. We used the phone

and visited a while and I asked Elaine if they needed any help there, that I

was just out of a job. They didn’t, and we went on to Holm Lodge and the rest of

the trip through the Park. I wish I had some pictures, but Viv had the only

camera, which was a movie camera of Dr. Allard’s. She took quite a few

pictures, but I saw them only once and I don’t know what happened to them. I do

remember we walked across the swinging bridge in the canyon[4] which was

posted with a “No Trespassing” sign. It was scary, as it swayed when we walked

on it. I suppose that was a challenge of some kind to do that, and besides it

gave us a real good look up the canyon. I also remember hand feeding a bear,

which was one of the pictures. Stupid kid—it’s a wonder I still have two hands!

The bears were more used to that then, though, and they weren’t as dangerous as

they are now. We saw most everything there was to see in the Park—went to dances

at night, moonlight picnics, horseback rides, etc. with the kids who worked up

there. It was a fun week.

A few days after returning from the Park, I had a telegram from Elaine saying she now needed some help. So I packed up and took the train to Cody. Having met so briefly the evening we were at the Trail Shop, neither your Dad[5] nor I remembered much what the other looked like. And he didn’t meet the train either, as he had business to attend to, so sent Mrs. Kid Wilson up to meet me in a taxi. She didn’t know who she was looking for and hardly recognized me from your Dad’s description, but we got together and met your Dad in Cody, and on to the Trail Shop.

Elaine

and Harry were “partners” with your Dad for that summer. I don’t know the

particulars of their arrangement—we all got along very well with the work,

which, as most of you know, was pretty grueling, with long hours and very

little time off. Besides your Dad and Elaine and Harry, there were you four

Sherwin children, ranging in age from 13 to 9—Virginia, Ted, Clifford, and

Betty. By and large (whatever that means) you were good kids and did your share

of the work too, the boys tending gas, getting wood for the cabins, gathering

and selling elk and deer antlers; the girls helping with the cabins, dishes,

waiting on tables, etc. Much work but we had some fun too.

Elaine

and Harry were “partners” with your Dad for that summer. I don’t know the

particulars of their arrangement—we all got along very well with the work,

which, as most of you know, was pretty grueling, with long hours and very

little time off. Besides your Dad and Elaine and Harry, there were you four

Sherwin children, ranging in age from 13 to 9—Virginia, Ted, Clifford, and

Betty. By and large (whatever that means) you were good kids and did your share

of the work too, the boys tending gas, getting wood for the cabins, gathering

and selling elk and deer antlers; the girls helping with the cabins, dishes,

waiting on tables, etc. Much work but we had some fun too.

Space was very limited, the house having but a small living room, two small bedrooms, kitchen and back porch. No bathroom at that time, and for many years more. Harry and Elaine slept in the back bedroom, the girls and I in the other. The boys slept on a sofa bed in the living room, where, as Clifford put it, “the sheets haven’t been changed since we had the itch!” [Wylie] slept on a cot out in the filling station. Public rest rooms, which we used also, were in another building with four toilet stalls and a shower in each side. The “big front room” was for the business, and was a dining room, souvenir shop, pop, candy and grocery store, and, of course, the office for the cabins and filling station, which were the main parts of the business.

Yellowstone Park busses made a rest stop twice a day, in the morning going up and in the afternoon going down—not the same busses, however. They bought quantities of cold drinks, ice cream and souvenirs. It took all hands working fast to wait on them in the 15 minutes or so that they were there.

As the summer progressed, it became evident that the 3-way partnership would not survive; the main difficulty being that Harry was prone to take over, and [Wylie] was not going to allow it. So at the close of business that fall, Harry and Elaine left. I stayed on, making trips now and then back to Billings and the ranch.

[Wylie] and I had been “romancing” a bit during the summer, but when the work slowed down we began to think more seriously and soon decided to get married. As your dad always said, “Nina said it would be a cold day in January when she married me!”—and was it ever! 30-below and lots of snow. We were married at the Lutheran Church Rectory, on January 18, 1930, with part of my family attending. Viv had a wedding supper afterward at our apartment and later that evening we left on the train for Denver. Budd and Chella rode down horseback that day to stay with you kids while we were gone. It was so cold that the chickens froze their feet and they had to be killed. We didn’t keep chickens too long after that, but did have a cow for several years.

It was cold and stormy in Denver, too, but we saw a few of the sights and did attend the Stock Show, which seemed to be the thing to do in Denver in January. Back to the Trail Shop within a week, and I was a wife and “instant mother” to four children—a role I have never regretted, as I had had time to know and love each and every one of you. I had become “Mama Bear”, even before the marriage, especially to Virginia, who originated the term. Not having anything to do with the aforementioned, I remember one day in town, a lady referred to us—Virginia, Betty and I—as “The Sherwin Girls”, then was embarrassed after she’d said it. But we did enjoy each other’s company, and I didn’t feel very old at the time. I was 24 that February.

The Trail Shop in those years was quite primitive and had an outdoor privy except in the summer when water was more available and we could use the restrooms like the tourists. The water supply was from Canyon Creek via a small ditch to two cisterns, then piped down to the house and restrooms. Once in a while it was warm enough in the winter so the cisterns could be filled from the creek. But if not, the cisterns went dry and water had to be carried in buckets from the river. So we always had to be careful in using water. We took baths in a round tin tub, saved the water to soak and wash clothes in, then at last to mop the floor with!

The sleeping arrangements were changed now, with Virginia and Betty having the back bedroom, Wylie and I the other one, and the boys at first in the living room, and later in #7, off the laundry room.

Summers were pretty grueling—no one knew what an 8 hour day was then. It was up early to serve breakfast, then lunches and dinners, never knowing how many or few there would be. As mentioned above, the busses took all hands for the time they were there, twice a day. The bottled drinks had to be put in the pop cooler, which had to be iced. Ice cream had to be made in huge batches at least once a day and sometimes twice. This was packed in ice, and turned by a belt run with electricity produced by the Delco plant and windmill back of the shop building.[6] The Delco plant also supplied lights and power for the house and cabins[7], and worked very well most of the time. When it did break down we had to have someone from town come up and work on it, sometimes all night.

The cabins were also very primitive at that time. The furnishings consisting of a double bed, two chairs, a fold-down wall table and a small flat topped heating stove which could be used for some limited cooking. Wood had to be furnished for these, of course. Travelers brought their own bedding, including sheets and pillows. This took up much room in their cars and the practice was soon discontinued.

One of the big and necessary jobs of winter was putting up the ice. The neighborhood men would get together and decide the time and place, then gather with their tools, pickups, etc. Large rectangular chunks were cut with an ice saw, lifted from the water with ice tongs and loaded onto pickups or sometimes sleighs[8] and hauled to each one’s home to be transferred to an ice house. These chunks of ice were then covered with sawdust, in between layers and on top and bottom, which kept the ice from melting. The women also got together bringing food to each other’s places for the ice crew, like the threshing crews in grain country. This was really hard work, but a social time to look forward to also for both men and women.

Wood gathering was another necessary chore, but I don’t seem to remember much about that for some reason, perhaps because each one mostly did his own.

Winter was the “social season” and we enjoyed our frequent gatherings. There were “the eight of us” as Chella always said: The Halls, Martins, Spencers and Sherwins. We would get together to listen to mystery stories on the radio (this was before TV, of course) and play games like charades, Bird, Beast & Fish, etc. We didn’t play cards much at that time. We always had dinner wherever we went. There were many dances at the schoolhouse which were really fun. All the kids went to these also. The music was mostly local and we would take up a collection for their pay. A midnight lunch was part of the fun—sandwiches, cake, and coffee, brought and served by the women. All pitched in to clean up afterward.

We also had the Wapiti Women’s Club, which met once a month, at noon. We had dinner then, not just refreshments, as we do now. The hostess furnished the meat and potatoes, coffee or tea, the others took turns bringing a vegetable, salad, rolls and dessert. If the person who was to bring something didn’t show up, the hostess had to scurry around and produce it herself, which became a good reason for later changing to lighter refreshments. At first, I was one of the youngest members of the Club, now I’m almost the oldest. Time does go by!

In the early ‘30s, the highway to the Park was being widened and improved, and most of the road crew stayed in the cabins at the Trail Shop and boarded with us. That meant early breakfasts, lunches to put up and dinner at night. As I remember there were 12-15 men. This was quite a lot of work, too, but at least we knew how many there would be for meals, in contrast to the tourist business.

All four of [the] older children attended Wapiti School through the 8th grade. Virginia stayed with [her] grandparents in Lovell the first year of high school, and part of the second year—the remainder of that year with Ted and Francine Huntington. Ted stayed with the grandparents his first year of high school also. Virginia’s senior year, all four had an apartment together in Cody. That was 1934 and Virginia and Wilber were married that May. (More about that later) After that, Ted and Clifford stayed with Virg and Wilber and with Grandma Edwards.[9] Betty worked for her room and board at Bruce’s and Decker’s. This may not be entirely correct, but somewhere near.

Soon after graduation, on May 23rd, Virginia and Wilber [Scholes] were married in Billings. We did not attend (too busy) but my sister Vivian did the honors for the family. The newlyweds lived in Cody for a few years, Wilber beginning a long and successful career with Safeway. On july 2, 1936, a great event occurred: the birth of their daughter, Nina Jean. Everyone was elated and she was a sweetheart right from the start. She also made me a grandmother before I was a mother! I was proud and touched that she was named after me, in part.

Virginia and Wilber moved to Hardin [Montana] about 1938, then to Laurel, Billings, Red Lodge, etc., with Safeway. After graduation from high school in 1935, Ted attended the University of Wyoming at Laramie, coming home in the summers. Clifford, after a year working at Holm Lodge, attended the Montana School of Mines at Butte. Betty was home for a while after graduating from high school. She was my friend and companion while I was pregnant. We did lots of walking during that fall and winter. Wylie and Clifford were getting out posts up the river and we would get their breakfast, put up the lunches, then ride up [with them] to about Nameit Creek and walk back from there. Then we’d have our breakfast, having worked up a good appetite. We’d eat, visit, look at catalogs and take it easy, having had our exercise for the day. One walk we took was across the ice on the river and over to Missy Lewis’s. That was almost too far, and about the last one we took.

The month before Russ was born, in fact on my birthday, February 9th, I was in the hospital with pneumonia. Wylie had had it too and was released from the hospital about the time I went in. As there was a lot of deep coughing, there was some concern about my having a premature birth, but that fortunately did not occur. I will remember the crude arrangement they had in the hospital at that time for treating pneumonia. The main treatment was to breathe steam several times a day. For this, there was a hot plate with a kettle of boiling water and a hood or mask to the mouth and nose to bring in and hold the steam. This hospital was an old 3-story house, converted to hospital use—very inconvenient, with long winding stairs to climb. The head of the hospital, and head nurse, was Theresa Worrall and my doctor was Dr. Victor Daken. One evening while I was still there, Virginia brought me some fruit Jello as a special treat. I ate it and enjoyed it, but with all the coughing, it came back up and I’ve never cared for fruit Jello since—sorry about that, Virg! Anyway, I recovered and went home.

On March 26, 1937, early in the morning, I awoke and felt this rush of warm wetness and knew the water sac had broken. So we scurried around and got to the hospital again. You were supposed to arrive in April, Russ, but you were ready to get out into the world, so you came two weeks early, saving me some anxious last days. But, after deciding to come early, you took your own sweet time about getting born, so it was about ten o’clock that night before you finally arrived. And great was the rejoicing throughout the land! After seven years, we had a baby, my first, and only—what a joy, Shoog. You were fairly small, weighing only 6 lbs. 2 oz., but perfect in every way and looking like miniature Wylie. The older children welcomed you as their little brother, though you all wouldn’t be together very much.

Caring for a baby, with all the baths, bottle sterilizing, baby clothes and diapers was no easy task without running water, but we managed to get through that stage and you weren’t too hard to potty train, Russ, when that time came. You walked for some time hanging onto things, and you were 15 months old when you decided to let go and strike out on your own. You were so pleased with yourself (so were we!) that you just laughed and took off like you’d been doing it for months.

I’m aware that I keep changing tenses in this narrative, but it’s easier that way, so I guess you will just have to put up with it.

The rest is fairly current and within the memories (oh, would that mine were clearer!) of all of you, except some of your baby and young boyhood years, Russ. You attended Wapiti School also, through the 7th grade, with a variety of teachers, mostly good, a few not so outstanding. You were a good student and pretty satisfactory in deportment, as it was called on my report cards—probably called attitude on ours. I’m sorry we didn’t save some of your report cards, but that did not occur to us at that time. Sometimes I have to wonder about some of the things we didn’t save and others that we did.

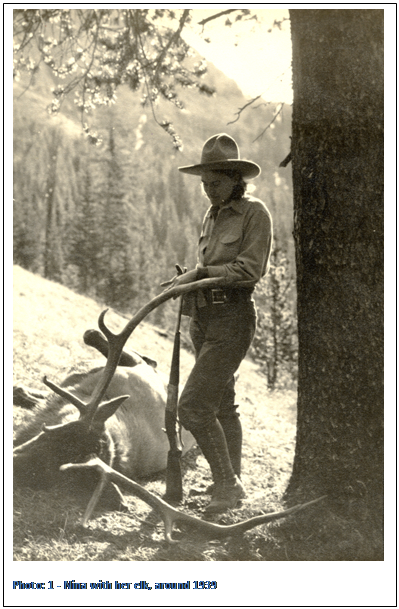

During some of your younger years, Russ, your Dad and I went on a few hunting trips into the Thorofare with Budd and Chella Hall. Your Aunt Hildred stayed with you those times, which really enabled us to go, as we wouldn’t have left you with just anyone. You were aways so good about our leaving, whether it was just for an evening or a 2-week trip. You would wave and smile and say “have a good time”—you always made your “a” sounds as “ay” instead of a flat “ah”.

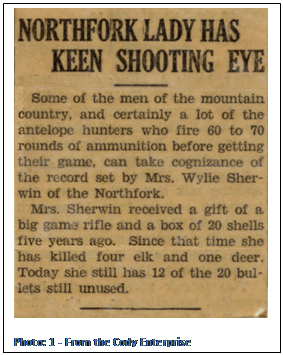

The hunting trips were something I had never expected to experience. They were a little tough, but fun, too, and certainly a different experience than most women have. We would spend two nights going in, sleeping out in the open in sleeping bags, no tepees or tents on the way in, and we cooked over bonfires. It saved time and was less work that way, for the men, anyway. In camp, of course, we had tepees to sleep in, and a big tent set up as living quarters; stove to cook on, panniers for cupboards to put canned goods in. Chella and I would set up these wooden boxes (the panniers without their covers) and put the cans in. Every can I put in, Chella would move to some other place! But we didn’t argue about it and got along with each other remarkably well, all of us, and enjoyed the trips immensely. I regretted having my first set of elk antlers sold by mistake, but don’t know what I would be doing with them now, anyway. I have the picture of me and the elk, so that’s better than having the antlers. It was a big bull elk with a very satisfactory set of antlers, or rack as they say. I was a pretty good shot and usually was able to get my game, after proper stalking with your Dad, who was a very good guide. He had an unerring sense of direction and always knew where he was and where camp was. Budd wasn’t really that good, but it was his outfit, except for our own two horses, so he was the Boss. This bull was taken on the second trip to the Thorofare, the first being a disaster right from the start, so of course, I must tell you about it.

We

started from the Trail Shop about 10 AM on a rainy, foggy day, going over Table

Mountain (the only time we ever went that way, the others always over Eagle

Pass). The fog was really thick as we went up the mountain and soon your Dad

realized that something was wrong. We were back-tracking and going back down

our side of the mountain. So he yelled at Budd to the front of the string and

told him that. Budd didn’t want to believe that, but soon had to from the

evidence of our tracks on the way up. We just made it to the other side of the

mountain that evening before we had to camp. Next day on to, and up, the

Ishawooa Trail on the Southfork side. At the top of the pass we were hit with a

real blizzard and traveled in that to our camp site on Open Creek. It let up enough

so we could get camp set up for the night and something to eat. We improved the

camp some the next day.

We

started from the Trail Shop about 10 AM on a rainy, foggy day, going over Table

Mountain (the only time we ever went that way, the others always over Eagle

Pass). The fog was really thick as we went up the mountain and soon your Dad

realized that something was wrong. We were back-tracking and going back down

our side of the mountain. So he yelled at Budd to the front of the string and

told him that. Budd didn’t want to believe that, but soon had to from the

evidence of our tracks on the way up. We just made it to the other side of the

mountain that evening before we had to camp. Next day on to, and up, the

Ishawooa Trail on the Southfork side. At the top of the pass we were hit with a

real blizzard and traveled in that to our camp site on Open Creek. It let up enough

so we could get camp set up for the night and something to eat. We improved the

camp some the next day.

For all the five or six days we were there, there was fog. We would hear the elk bugle, but they would not be there when we approached where we thought they were. Finally Budd spotted a cow lying down in the brush and shot it. Well, that turned out to be a muley bull (one without antlers), the meat from which is not high on anyone’s list of taste thrills! That ended our stay there and we headed out for Eagle Pass. We camped once on the way in the snow, and while it was snowing. The second night we made it over the pass in 3 feet of snow, to Earl Crouch’s cabin on Eagle Creek, a most welcome sight. The tents and all the packs were wet and frozen so we couldn’t have set them up without a great deal of difficulty. Budd and I had both been sick all that day, so getting inside the shelter of a cabin was the next thing to Heaven. (I’ve never been There, but I intend to go sometime!)

Cabins

like that were never locked and there was wood and some provisions always on

hand. Whoever used the cabins were supoosed to leave wood, split and ready, to

replace what was used, and also food supplies, if possible. We made it home the

next day, but I have wondered since why I ever thought I should go again. We

did make two more trips into the Thorofare, both really enjoyable and I’m glad

I did decide to go again. I certainly wouldn’t want to do it now!

Cabins

like that were never locked and there was wood and some provisions always on

hand. Whoever used the cabins were supoosed to leave wood, split and ready, to

replace what was used, and also food supplies, if possible. We made it home the

next day, but I have wondered since why I ever thought I should go again. We

did make two more trips into the Thorofare, both really enjoyable and I’m glad

I did decide to go again. I certainly wouldn’t want to do it now!

In the meantime, back at the ranch—

For the 8th grade, Russ, we decided it would be better for you to be in town. We made arrangements for you to stay at Rickells. You shared a room there with Brad McClellan who was also in the 8th grade. You stayed there the next year too, with Mike as your roommate, as Brad had gone to Military School. Not as good as with Brad, but you both got through the year all right. After that, you could drive, and drove the pickup back and forth.[10]

And now we really are in more or less current times. I can’t go into the marriages of each of you, or the births of all the grandchildren and great grandchildren, momentous and joyful as they all were. I had to write about Nina Jean, as she was the first-born in the family, and as I said, the one who made me a grandmother before I was a mother.

This has been a little trip down Memory Lane for me, and for you, a little knowledge of my life and times, and perhaps some insight into what makes me me.

My love to you, each and every one, family and in-laws. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world!

Mom

had a stroke in August, 1993, just one day after our last family reunion at Lee

Scholes home in Pleasanton, California. She recovered enough to be able to walk

fairly soon, but was never able to speak or write after that, though she could

understand everything and read perfectly well. She lived a little more than a

year after that in an assisted living facility, The Forum, in Cupertino,

California, just a few miles from where we lived in Sunnyvale. I was able to

visit her nearly every day of that year, and despite her inability to speak, she

remained in good health and good cheer the entire time.

Mom

had a stroke in August, 1993, just one day after our last family reunion at Lee

Scholes home in Pleasanton, California. She recovered enough to be able to walk

fairly soon, but was never able to speak or write after that, though she could

understand everything and read perfectly well. She lived a little more than a

year after that in an assisted living facility, The Forum, in Cupertino,

California, just a few miles from where we lived in Sunnyvale. I was able to

visit her nearly every day of that year, and despite her inability to speak, she

remained in good health and good cheer the entire time.